“Stella faced difficulties in math and was very hungry for attention and approval. I gave her some of that, and gave her little challenges—sort of brainteaser math problems that I wouldn’t reveal the answers to.” At home, Stella would figure out about half of the problems and would feel proud to show off her work the following week.

Sometimes academic mentors from Boston Partners in Education never get to see the immediate results of their work with students. If they do see results, it is usually after a few years. One hour a week, however, can make a rippling impact. One hour is enough to fill gaps in a student’s knowledge, to inspire a student’s confidence, and to build a relationship that goes beyond classroom walls.

Robert Denn has been an academic mentor since his retirement over 12 years ago. He first began volunteering by reading to kids as part of a program run by Generations Inc. After the Headmaster for the school discontinued the program, Denn discovered Boston Partners in Education.

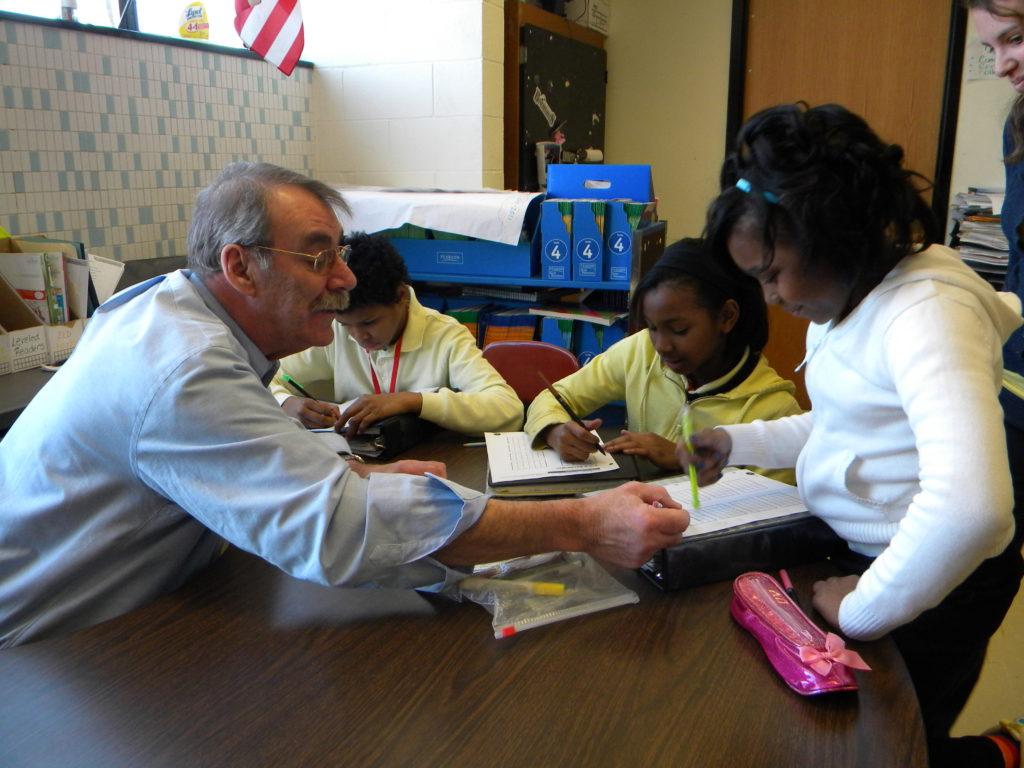

Denn joined the burgeoning Math Rules! Program (now referred to as Accelerate Math) at the Marshall School. He was paired with a group of four students during class time to provide a little extra help on that day’s lesson. “I’d show up one or two days a week in their math class,” he said. The teacher would brief him on whatever the issues of the day were, and for the remainder of the hour, he and his group of students would sit and work on the problems together.

Denn wasn’t sure if an hour a week made a big difference, especially for students who struggled most in math. Recently, he’s been matched with students who are more in the middle of the learning curve and the teacher had high hopes he could push them into the top of the class. “I seem to think that’s working,” said Denn. “But I don’t think I can prove it.”

Denn recalled a student, Stella, from the Warren-Prescott school who faced difficulties in math. “She was very hungry for attention and approval. I gave her some of that, and gave her little challenges—sort of brainteaser math problems that I wouldn’t reveal the answers to,” he said. At home, Stella would figure out about half of the problems and would feel proud to show off her work the following week.

Still, Denn wasn’t sure if he was making a difference in her life. “At the end of the year I said goodbye to my students. I came back the following year and had different kids to mentor. I thought I would never run into Stella again.”

A few months later while walking down the halls of the Warren-Prescott school, Denn was pleasantly surprised to be greeted by Stella. “Hello Stella,” he replied in return. She was blown away that he remembered her name.

Another week, a young boy Denn did not recognize approached him and asked, “Are you Mr. Denn?” Denn responded, and the boy revealed that Stella is his big sister. “The fact that her little brother knows me was very touching,” he recalled.

“Students are always asking me why I do this. They’re always asking if I get paid, and they can’t imagine why anyone would willingly spend time with them. I tell them because it’s fun and because I like to see their faces when they learn something.”

Denn remains fascinated by the fact that the children are so unaccustomed to the idea of an adult taking a personal interest in their education, but it’s exactly that kind of interest that students can use to build confidence. “I run into kids that give me a big hello and they always seem to be surprised that I remember who they are,” Denn said.

“They’re [students] always asking me why I do this. They’re always asking if I get paid, and they’re astonished when I say I don’t. They can’t imagine why anyone would willingly spend time with them,” Denn shares. “I tell them because it’s fun, because I like to see their faces when they learn something, so let’s stop gabbing and do some work!”

Despite his initial doubts, Denn is becoming aware of the difference he’s making in the lives of students like Stella. One hour in the classroom may not seem like much, yet over many weeks, the resulting relationship can mean more to a student than one could ever imagine.