In 1966, there were no libraries in Boston public elementary and junior high schools. This was due in part because in many schools, teachers could not receive funding for new books in their classrooms, let alone enough to fill a lending library. The school library was a fairly new idea at the time, even though the benefits for children may now seem obvious.

The book Death at an Early Age, by former school teacher Jonathan Kozol shocked and catalyzed a small group of women in Boston to begin searching for ways to improve the degrading environment that many of the children faced. The federal government was awarding grants under ESEA Title II, which provided funds to purchase the books and furniture needed for a library. The first school library in Boston, constructed in a junior high school in Charlestown, received materials and novels donated by the Boston Public Library, the Museum of Science, and the Massachusetts Bureau of Library extension. In total, 225 books were donated or acquired, featuring both nonfiction and fiction.

The question that remained was, who would staff the library?

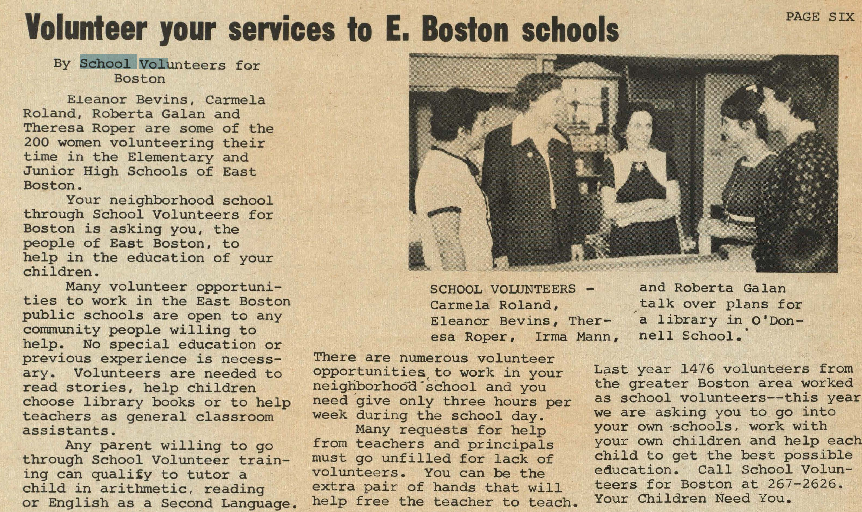

Boston Partners in Education, then called School Volunteers for Boston (SVB), was a brand new program in 1966 and struggled to build trust and rapport with the Boston Public Schools.

SVB found a way to bring its first volunteers into the schools through what would eventually become the School Library Program. Edna Koretsky, SVB’s Executive Director, nominated Polly Kaufman and Margaret Brown, two of her best volunteers, to head the Library Program for Boston Public Schools.

Kaufman and Brown were both determined that the library materials represented the students who would read them. This was just a few years after Kozol was fired from BPS for teaching a Langston Hughes poem to his class. The Library Program felt an urgency to connect students to reading in the same way that Kozol had; to bring in books that truly reflected the world and experience that black and brown city students knew.

In her account of the early years of the School Library Program, Kaufman writes:

“It was a time of a kind of mass judgment against the Boston Public Schools by Civil rights groups in the city allied with ‘white liberal’ groups in the suburbs. Two years before, in the wake of the Kennedy assassination, righteous cries against de facto segregation had led to EXODUS, an organization that busses black students from Roxbury to other Boston Schools…The Racial Imbalance law was a product of these times as were two important books that served as the Silent Spring of the movement: Kozol’s Death at an Early Age, and Schrag’s Village School Downtown.”

Edna Koretsky eventually reached an agreement with BPS to allow volunteers, so long as a volunteer didn’t have a child in that specific school. This attitude seems surprising now, yet it reveals a deeply ingrained mistrust that BPS once held for outside influences–the same influences which inspired SVB and the Library Program.

For SVB, gaining the cooperation of the system was only half the problem. Koretsky still had to locate a point of entry, a specific school that was actually willing to accept strangers into their doors. The new library being built in the Charlestown school was exactly the opportunity she sought. In this case, Koretsky made a deal with the school principal: he would allow her volunteers into classrooms for any number of projects, as long as the construction of a library was one of them. Assisting with the construction and staffing of school libraries was an incredibly valuable addition to the BPS system, and created a pathway for Koretsky to show the city how much SVB could help.

Finally, Koretsky convinced the principal and BPS that the library could not succeed if staffed solely by her volunteers. The program needed to be run by a professional librarian. She nominated Margaret Brown, who would become a dedicated leader and tackle many of the program’s future challenges. Kaufman described her co-leader as, “a person with charismatic personality and a zeal for reading and libraries that had been honed in the children’s rooms of the New York Public Library in the Depression, when the immigrant children lined up waiting for the return of a picture book.”

Most of these volunteers were housewives, mothers, and members of local churches. Mike Redding, who would eventually become one of SVB’s most loyal employees, began her work as a library volunteer. She recalls the direction of Polly and Margaret during library construction:

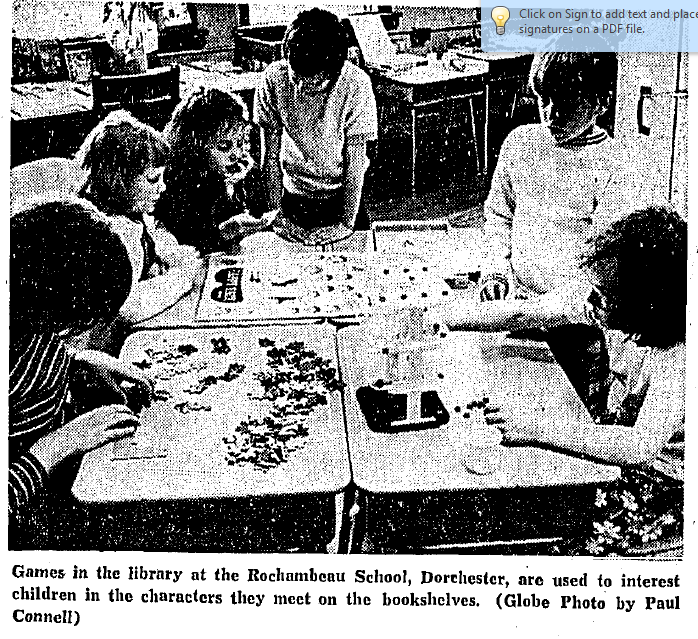

“The first thing I remember [was] a description of what you needed to do to make the library gorgeous. I remember them saying ‘You want to use the primary colors. There were folding bookshelves that had been designed by Thomas McCauliff, who was one of the principals and superintendents. It had been put together by the woodworking students …We ended up getting bright red, bright blue and bright yellow, and painting them that way. The custodian really was very interested in the project and he brought in a couple of tree trunks which served as incidental tables and stools. And if you had windows you made brightly colored curtains. It was just really meant to be a very positive, very bright place.”

Redding’s account demonstrates the resourcefulness of the Library Program. Libraries were built in schools wherever there was space. Sometimes they would be on stages, in basements, in large closets, or in abandoned classrooms. Redding recalled how quickly the school’s attitude regarding SVB changed as a result of these projects.

“For one thing it helped us to get to know the teacher’s better and vice versa. I remember when we started, at the George Frisbee Hoar School in South Boston. I can remember that the principal had been dying to have a library set up. Not all the teachers were as enthusiastic. One teacher on our first day said, ‘It’s a great idea but it’s never going to work.’ Well, it really did! And, the principal swore that the test scores went up because of the access to the library. And we got to know all the teachers. It was great.”

The Charlestown library became the base of operations and training in the first year of the School Library Program. Volunteers worked with Margaret there until they were sufficiently trained in library science, then began their own libraries in different schools. As the program grew, Koretsky insisted that the Library Program be considered the project and property of Boston Public Schools, though SVB would continue to provide volunteers for many years.

(Check back next week for Part Two of the Library Program)